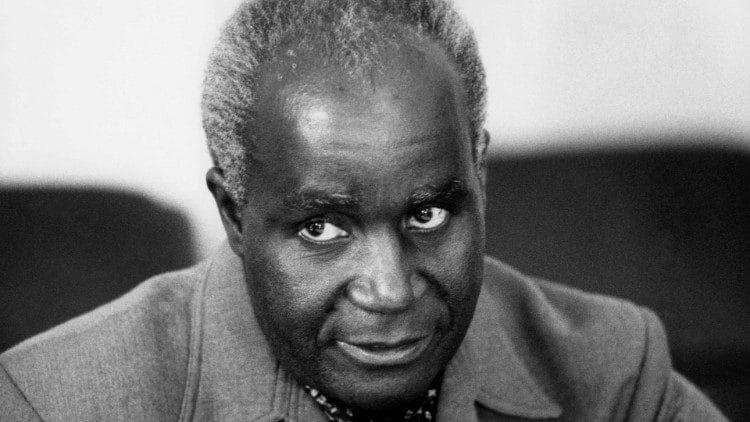

Kenneth David Kaunda was a Pan-African nationalist who served as the first President of the Republic of Zambia from 1964 to 1991. After leading his country to independence from British colonial rule, Kaunda set out to forge a united nation guided by his philosophy of Zambian humanism—an ideology rooted in African values, Christian ethics, and social justice. His rallying cry, “One Zambia, One Nation,” became both a political vision and a national identity.

Kaunda was deeply committed to African liberation and played a quiet but pivotal role in the fight against apartheid and colonial oppression in Southern African countries, including Zimbabwe, South Africa, Namibia and Mozambique. Under his leadership, Zambia became a safe haven for exiled freedom fighters from these countries while simultaneously pursuing ambitious efforts to expand education, healthcare and economic independence through state-led development.

Though widely respected for his diplomacy and moral leadership, Kaunda’s later years in power were marked by growing economic hardship and political unrest. In 1991, after nearly three decades in office, he peacefully stepped down following Zambia’s first multi-party elections—a rare and dignified transition in the region at the time. Kaunda’s role in Southern Africa’s liberation struggle and his post-presidency advocacy for peace and HIV/AIDS awareness, especially cemented his reputation as a humble yet visionary leader.

Early Life

On the 28th of April 1924, Kenneth Kaunda was born in Lubwa, Zambia, into a family of educational tutors. Notably, his mother was the first African woman to teach in colonial Zambia while his father—who was of Malawian origin—was a schoolteacher. Both parents taught in Northern Zambia where Kenneth Kaunda himself received his early education in the early 1940s.

In colonial Zambia, having an education meant achieving a measure of middle-class status which bequeathed on its holder, a privilege to teach. Hence, Kaunda began to teach just as several other Zambians with the same status. He taught first in colonial Zambia and then in Tanganyika, now known as Tanzania.

A Strategic Fight Against Colonialism

In the late 1940s, Kaunda returned to Zambia with a vision to fight colonial rule. This marked his intentional foray into Zambia’s political space, as an interpreter and adviser on African affairs to a notable member of a Legislative Council called Sir Steward Gore-Browne. During this period, Kaunda garnered extensive political knowledge and skill which became very useful when he joined the first major anticolonial organisation in Northern Rhodesia, the African National Congress (ANC). Gradually, Kaunda progressed in this political space, becoming the group’s secretary-general and chief organising officer under the leadership of Harry Nkumbula.

Between 1958 and 1959, the leadership of the ANC clashed. This clash occurred between Nkumbula and Kaunda. Kaunda, having learnt much of the ANC’s structure and strategies, used them to establish the Zambian African National Congress (ZANC), eventually becoming its president. Over time, the political group became indispensable to Kaunda’s plans to fight against colonialism in Zambia.

Memorably, the group was instrumental as a major force Kaunda used to fight a federation policy that the British government sought to impose at the time. This policy would have led to the concentration of powers in the hands of a white minority. In an attempt to stop this plan, Kaunda used ZANC to orchestrate a non-violent protest against the policy, an act that led to his arrest by the British government. However, the broader stance of ZANC was increasingly confrontational as its rhetoric and actions reflected growing frustration over colonial rule. In March 1959, the party was formally banned by the British colonial government, and Kaunda was sentenced to nine months in prison, which he served in Lusaka and then in Salisbury (now Harare).

Kaunda’s bold resistance, however, brought about two major outcomes: First, the British government agreed to discard the proposed policy; Second, Kaunda became a national hero to the Zambian people. This orchestrated a revolutionary movement in the history of Zambia, garnering nationwide support for Zambia’s independence.

On the 8th of January, 1960, Kaunda was released from prison, and was immediately elected the president of the United National Party (UNIP) earlier formed as a successor to Kaunda’s ZANC in 1959 by one Mainza Chona and a group of nationalists with similar ideologies. As a result of Kaunda’s reputation by this time, UNIP enjoyed sporadic growth, swelling in ranks to a profound 300,000 members by mid-1960, and signifying an undeniable signal of where the national spirit was headed.

From then on, Kaunda emerged as the unshakable face of Zambia’s independence movement. In 1960, he travelled to Atlanta, USA, to meet with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., drawing inspiration from the American civil rights leader’s nonviolent resistance strategies. Inspired and emboldened, upon returning to Zambia, Kaunda launched the Cha-cha-cha campaign in July 1961—a civil disobedience movement in the Northern Province that relied on arson, road blockades, and mass protests to disrupt colonial administration and encourage national consciousness.

By December 1960, Kaunda’s reputation had grown monumentally, alongside that of several other UNIP leaders, earning him the honour of being invited by British colonial authorities to London, to participate in discussions geared towards anti-colonialism in Zambia. The following year, the British government officially announced that the process of transitioning Zambia to independence would begin.

In 1962, the first major elections toward that goal took place, featuring UNIP and ANC among other parties. Despite constitutional proposals that heavily favoured European settlers, UNIP and ANC emerged dominant with the former securing 15 out of the 37 available seats in the new Legislative Council—enough to form a coalition government with its rivals in the ANC. The tide had clearly turned, and the countdown to full independence had begun.

Overall, UNIP’s success was attributed to Kaunda’s leadership. He had diplomatically allayed the European settlers’ fears that their interests would be disregarded while also quelling factionalism in large sections of the region. In 1964, Zambia was granted independence with Kaunda at the forefront, negotiating newer constitutional terms. In the same year, Kaunda became Zambia’s first Prime Minister and eventually its President in 1968, after becoming a republic.

Presidency

With independence won and the hopes of a nation resting on his shoulders, Kenneth Kaunda set out to shape Zambia into a unified, stable, and independent republic. One of the earliest and most delicate challenges he faced was tribalism—a deeply rooted issue that threatened the national unity of Zambia. Through careful dialogue, inclusive policies, and his unrelenting emphasis on “One Zambia, One Nation,” Kaunda managed to avoid the kind of tribal civil conflict that plagued many other newly independent African states.

Yet unity came at a cost. In 1972—immediately after the tense and sometimes violent elections of 1968—Kaunda introduced one-party rule. The following year, a new constitution was enacted that established Kaunda’s party—the United National Independence Party (UNIP)—as Zambia’s sole legal political party, effectively silencing formal opposition.

Economically, Kaunda steered Zambia toward state-led socialism, with an emphasis on national control of key industries. This led to major government acquisitions of national resources including a majority stake in the country’s copper mines, which had long been controlled by foreign corporations.

While this move was meant to empower Zambians and redirect profits into national development, it also left the country dangerously reliant on copper exports as it became Zambia’s sole revenue generator. In yet another move that ultimately crippled the success of Kaunda’s government, agriculture was heavily sidelined—yet heavily subsidized urban food programs continued, further straining public finances. Simultaneously, the government also tried to gain control of farmlands and with these series of decisions, came a growing dislike for Kaunda’s leadership. Understandably, Kaunda’s good intentions were evident, however without experience and effective strategies, this goodwill ultimately became malicious towards the people of Zambia, sparking an outrage nationwide.

The effects of these policies on Zambia were disastrous especially after global copper prices began to fall and crude oil became the most sought commodity across the world. As a result, Zambia’s economy began a slow and painful decline. Living standards dropped, unemployment rose, and the social gains made in education and health related policies began to erode.

Despite the evident difficulties in his homeland, Kaunda remained committed to regional liberation struggles. Notably, he was among the first African leaders to impose economic sanctions on Southern Rhodesia—now known as Zimbabwe—a decision that crippled Zambia’s trade but established Kaunda’s moral stance. He was also highly instrumental to the cause of black nationalist fighters such as Joshua Nkomo’s forces, allowing them to operate from Zambian soil in the fight against white-minority rule. Though the economic cost was steep, Kaunda's unwavering support for liberation movements reflected his conviction that freedom for one African nation could not come at the expense of another’s oppression.

Amid growing unrest at home and escalating tensions across Zambia’s borders, Kaunda deepened his hold on power. Although he had not been overthrown or directly threatened with removal, he invoked emergency powers in 1976 as a preemptive move to maintain stability. Student protests, labor strikes, and disillusionment with the one-party system had begun to shake the foundations of his government, while external threats from hostile white-minority regimes further heightened the sense of insecurity. These emergency powers allowed Kaunda to detain opponents without trial, restrict press freedoms, and suppress political dissent—consolidating UNIP’s grip on the state under the justification of national unity and security.

With opposition parties banned under the one-party system, republican elections became largely symbolic. Kaunda was re-elected in uncontested, one-candidate polls in both 1978 and 1983, with the electorate voting 'yes' or 'no' to extend his presidency. These elections, held under the shadow of emergency powers and political repression, showcased his increasingly autocratic rule. During this period, several attempted coups were thwarted, reflecting growing discontent within sections of the military and political elite. Meanwhile, public confidence in his leadership continued to decline as corruption within state institutions deepened, food shortages worsened, and the economy—still heavily reliant on copper—continued to unravel.

By the end of the 1980s, a credible political opposition began to emerge, and public frustration could no longer be ignored. In 1990, recognising the growing demand for democratic reform, Kaunda legalised opposition parties and agreed to hold free elections. The following year, in a landmark moment for Zambian democracy, Frederick Chiluba’s Movement for Multiparty Democracy (MMD) won a decisive victory. Kaunda stepped down peacefully on November 2 1991—a truly laudable action, marking the end of an era—and earning international praise for his dignity and statesmanship in transition.

Kaunda’s Policies and Ideals in Governance: An Overview

Upon taking office, Kenneth Kaunda inherited a country with immense natural wealth but limited human development. At independence, Zambia had only a handful of university graduates and a sparse secondary education base. Understanding that no real sovereignty could exist without education, Kaunda invested heavily in building Zambia’s educational system. Schools multiplied, and under his leadership, children across the country were given basic learning materials free of charge. While parents contributed token fees and uniforms, the aim was clear: to cultivate a generation of educated Zambians who could lead their own future.

In 1966, the University of Zambia—a national effort built from grassroots contributions— officially opened its doors.. Kaunda became its first Chancellor, symbolising his commitment to education. Over the years, other institutions followed—from vocational colleges to teacher-training schools—creating a new academic landscape in the once-overlooked colony.

Economically, Kaunda adopted a form of African socialism he termed Zambian Humanism, blending Christian values, traditional communal ethics, and state-led development. Under this banner, he launched the Mulungushi Reforms in 1968, which brought Zambia’s key industries—particularly its foreign-owned copper mines—under state control. These nationalisation efforts, though rooted in self-reliance, ultimately tethered the nation’s fortunes too closely to a single volatile export. When copper prices crashed in the mid-1970s, Zambia’s economy unraveled. Ambitious development plans were shelved, debt soared, and living standards spiraled. By the 1980s, structural reforms were underway, but Kaunda’s cautious approach and resistance to rapid liberalisation limited their impact.

Politically, Kaunda’s belief in unity led him to declare Zambia a one-party state in 1973. While this move was meant to quell tribal divisions and political violence, it also concentrated power in his hands and eliminated meaningful opposition. Over time, elections became formalities, with Kaunda often running unopposed and winning by overwhelming margins. Yet through this system, he promoted an image of himself not as a dictator, but as a guiding father figure—deeply committed to peace, dialogue, and social unity.

Kaunda’s ideals, however, faced sharp criticism. His critics saw Zambian Humanism as overly paternalistic, and his style of governance, though peaceful, as increasingly authoritarian. However, opposition voices were suppressed, and political dissent was sidelined and Kaunda retained widespread respect for maintaining relative internal stability during an era when many African nations slid into coups and civil wars.

On the international stage, Kaunda emerged as a resolute anti-colonial voice. Zambia became a base for liberation movements fighting white minority regimes in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), South Africa, Namibia, Angola, and Mozambique. Though this solidarity came at a great economic cost—especially as Zambia’s trade routes were cut off by neighbouring regimes—Kaunda stood firm. He supported exiled leaders, hosted peace talks, and often mediated in regional conflicts. His alliances spanned continents: he worked closely with leaders from the United States and China, as well as the Soviet bloc and Non-Aligned Movement, always pressing for justice in southern Africa.

Yet his moral diplomacy was not without controversy. His request for sophisticated weaponry from Western allies was denied, pushing him to procure Soviet-made jets in the 1980s—moves that raised eyebrows in Washington but, for Kaunda, symbolised an unwavering commitment to protecting his people.

Fall from Power

By the end of the 1980s, Kenneth Kaunda's long rule stood at a crossroads. Years of economic decline, mounting debt, and political fatigue had eroded the once-solid foundation of the one-party state. In July 1990, frustration boiled over into violent riots in the capital city of Zambia, Lusaka, followed days later by a failed coup attempt. Though swiftly quelled, the uprising was symbolic: the grip of Kaunda’s United National Independence Party (UNIP) was loosening, and Zambia’s political future was being recast.

Kaunda initially responded by announcing a national referendum on whether to legalise other political parties, yet still argued for maintaining UNIP’s dominance, warning that multiparty democracy would reignite tribalism. But public pressure and the momentum of change quickly overtook this cautious stance. By September, he abandoned the referendum plan and instead endorsed constitutional reforms to end one-party rule. In December 1990, the amendments were signed into law. Multiparty elections were set for the following year.

In those elections, held in October 1991, Kaunda faced a formidable opponent in Frederick Chiluba, a trade unionist and leader of the newly formed Movement for Multiparty Democracy (MMD). The result was a landslide. Kaunda won only 24 percent of the vote. UNIP, once the only legal party, was reduced to a minority in Parliament. A controversial proposal to lease a quarter of Zambia’s land to an Indian guru in exchange for utopian agricultural development had become an unlikely campaign issue, casting further doubt on Kaunda’s judgment. On 2 November 1991, Kaunda formally handed over power—becoming one of Africa’s few founding presidents to relinquish office peacefully after electoral defeat.

It was a quiet end to a turbulent tenure, but one that reflected the very ideals Kaunda had long espoused: dialogue over violence, unity over division, and national interest over personal power.

Legacy

Kenneth Kaunda’s legacy is etched into the soul of Zambia. He was the teacher-turned-liberator who gave voice to a young nation’s hopes, preaching unity in a land of many tribes and walking with quiet conviction through the storms of history. His dream of “One Zambia, One Nation” was more than a slogan—it was a lifelong mission to hold together a fragile postcolonial state through dialogue, sacrifice, and moral clarity. He stood boldly against apartheid and white-minority rule, even when it meant hardship for his own people. Yet, like many who stayed too long, Kaunda’s later years in power were marked by economic decline, political repression, and growing public disillusionment. Still, when the time came, he chose peace over pride, stepping down with dignity and allowing democracy to take root. In the hearts of many Zambians, Kaunda, more affectionately referred to as KK throughout the country, remains more than a politician—he is a father figure, remembered with both love and lament, whose life embodied the struggle and spirit of a nation finding its way.

Oluwatetisimi Ariyo

Oluwatetisimi Ariyo is a seasoned writer with extensive experience crafting compelling and conversion-focused content for top global brands.

Leave a Comment

Sign in or become a Africa Rebirth. Unearthing Africa’s Past. Empowering Its Future member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.

Related News

Charwe Nehanda, Zimbabwe's Warrior Spiritual Leader at the Forefront of Zimbabwe's Anti-colonial Struggle

Sep 22, 2025

King Kabalega of Bunyoro and his Lonely Fight Against British Dominance in Uganda

Sep 22, 2025

The Great Life of Amílcar Cabral Was One of Struggle, Leadership, and Liberation

Aug 16, 2025