The Rwandan Genocide of 1994 is one of the darkest moments in modern history, immortalised in the hearts of those who witnessed it but also to the rest of the world through films like Hotel Rwanda. The genocide demonstrates how political manipulation and sheer hatred can destroy a nation. But the roots of this tragedy were planted long before the violence began. Colonial powers, especially Belgium, exploited divisions within Rwandan society and made them worse.

In this article, we will look at the events that led to the harrowing tragedy, how the genocide unfolded and how Rwanda was able to pick up the pieces afterwards.

The Colonial Seeds of Hatred

Before European colonisation, Rwandans lived under the Kingdom of Rwanda. This was a feudal society mostly governed by the Tutsi ruling class, though there were some Hutu chiefs. The groups ‘Hutu’, ‘Tutsi’, and ‘Twa’ were more about social class and occupation than ethnicity. People could move between these groups through wealth or status.

The Germans arrived in the late 19th century, and maintained the existing power structure to control resources without making big changes. But when the Belgians took over after World War I, they drastically changed Rwandan society. From 1918 onwards, they enforced stricter governance and solidified social divisions.

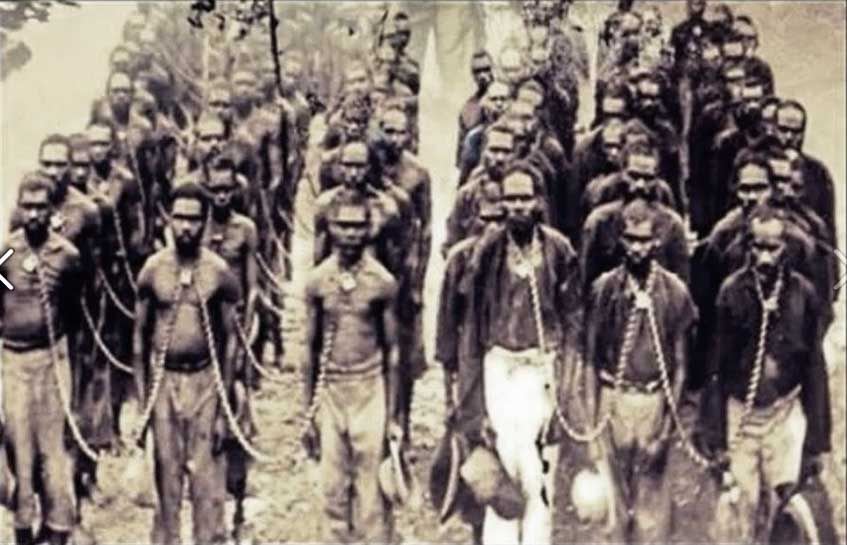

By 1933, the Belgian administration introduced identity cards that officially labelled locals as Hutu, Tutsi, or Twa. They believed the Tutsi were superior because of their so-called 'Hamitic' origins. This false theory claimed Tutsis were more ‘European-like’ in appearance and intelligence. As a result, the Belgians favoured Tutsis by giving them better education, government positions, and control over land.

The implementation of these identity cards was not just a tool for administrative control but a tool for segregation and social engineering. According to some historians, Belgium’s approach to identity documentation had roots in their experience with population control at home during the First World War.

Belgian authorities believed they were refining an orderly system of governance. In reality, they were planting the seeds of deep resentment. The cards reduced identity to rigid categories and stripped away the social fluidity that once existed. People were boxed into artificial constructs, and the lines between Tutsi, Hutu, and Twa were turned into unbreakable barriers. This practice paved the way for decades of discrimination and hatred.

The Road to Genocide

The imbalance created by the Belgians caused resentment among the Hutu majority. Tutsi chiefs, supported by the Belgians, often oppressed Hutu farmers. By the time Rwanda gained independence in 1962, tensions between Hutus and Tutsis were dangerously high. The Hutu Revolution of 1959 led to many Tutsis being killed or forced to leave the country.

Economic problems and political instability made things worse. The Hutu-led government that took power after independence discriminated against Tutsis. By the 1990s, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a Tutsi-led rebel group based in Uganda, was fighting to return to Rwanda. This sparked a civil war which went on for four gruelling years.

As the civil war dragged on, anti-Tutsi propaganda spread like wildfire. Extremist Hutu politicians and media outlets fuelled animosity by painting Tutsis as the enemy within. The divide-and-rule tactics of the Belgians had now evolved into an openly hostile political climate where violence against Tutsis was justified as self-preservation.

100 Days of Horror

On 6 April 1994, a plane carrying President Juvénal Habyarimana, a Hutu, was shot down while landing in Kigali, the Rwandan capital. Everyone on board died, including Burundian President Cyprien Ntaryamira, a fellow Hutu. This was the definitive trigger for the genocide.

Hutu extremists blamed the RPF while the RPF claimed that they were innocent and the Hutu had shot down the plane to provide a perfect excuse for what ensued. Nonetheless, under the leadership of Hutu Colonel Théoneste Bagosora, Hutu militias launched a campaign of mass murder. Over the next 100 days, over 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus were killed by the Hutu extremists.

The genocide was not just random violence. The government backed these Hutu militias, providing them with weapons and lists of targets. Political leaders used propaganda to encourage ordinary people to kill their neighbours. This hatred had been building for decades, rooted in the divisions created by Belgian rule.

Even more chilling, people who once shared food, laughter, and friendship became killers or victims overnight. Even familial ties were not enough to dissuade Hutu husbands from killing their Tutsi wives. Roadblocks were set up to check identity cards, and anyone labelled 'Tutsi' was murdered on the spot.

The Hutu extremists set up a radio station called Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM) in order to encourage people to ‘weed out the cockroaches’—the Tutsis. The broadcatsers told stories that highlighted and—some would argue—exaggerated the oppression the Tutsis subjected the Hutus to, thereby galvanising the violence. They even went as far as reading out names of prominent people who were to be killed.

Massacres occurred in schools, churches, hospitals and homes. Even sanctuaries like churches, which had previously been places of safety, became slaughterhouses. Tens of thousands of people seeking refuge in these buildings were mercilessly killed.

The international response was weak. The UN and Belgium had peacekeeping forces in Rwanda, but they did little to intervene. In fact, Belgian and most UN peacekeepers were pulled out after 10 Belgian soldiers were killed while protecting moderate Hutu Prime Minister Agathe Uwilingiyimana. Meanwhile, the French, who were allies of the Hutu government, sent a special force to evacuate their citizens and set up a ‘safe zone’.

The Aftermath

The genocide ended on 4 July 1994 when the RPF, backed by Uganda’s army, captured Kigali. But the aftermath was devastating. Millions of Hutus fled to neighbouring countries like Tanzania and DR Congo, fearing retaliation from the surviving Tutsis.

Some human rights groups say that the RPF indeed led some revenge attacks, killing thousands of Hutus, but the RPF denies this. Moreso, thousands of Hutu refugees in DR Congo died from a cholera outbreak.

Ironically, many Rwandans who fled the violence found refuge in European countries, including Belgium—the very nation whose colonial policies sowed seeds of discord. For many Rwandans, especially those in Belgium, the situation was bittersweet. They found safety and opportunities in a country linked to their homeland’s pain.

Figures like Dorcy Rugamba, a Rwandan playwright and actor, turned his trauma into art while living in Belgium. His works highlight themes of memory, identity, and reconciliation. Another figure, Marie Béatrice Umutesi, a writer and peace activist, has used her voice to criticise the world’s response to the genocide and highlight the struggles of refugees.

Belgium’s own reckoning with its colonial past adds another layer of irony. In 2024, a Belgian court acknowledged that the state committed crimes against humanity through the systematic abduction of mixed-race children in its former African colonies. This decision revealed the depth of Belgium’s colonial legacy, one that many Rwandans in the diaspora must reconcile with as they rebuild their lives.

Rebuilding from the Ashes

Since 1994, Rwanda has been trying to rebuild. Under Paul Kagame’s leadership, the government banned ethnic labels and promoted a unified Rwandan identity—Banyarwanda. But the impact of Belgian colonialism’s divisive legacy still lingers.

The Rwandan Genocide is a painful reminder of how colonial powers exploited identity to maintain control. It also shows the importance of unity and reconciliation in building a peaceful future. However, the healing process is far from over. The scars left by Belgian policies and the genocide itself are still felt by Rwandans, whether they remain in the country or have found new homes abroad.