On 2nd October, 1958, the West African country of Guinea won full independence from France. This was unprecedented as other French colonies on the continent had opted for partial independence which sustained their membership in the French Community, a political entity that was established to ensure France’s continued control of its African countries following “independence.”

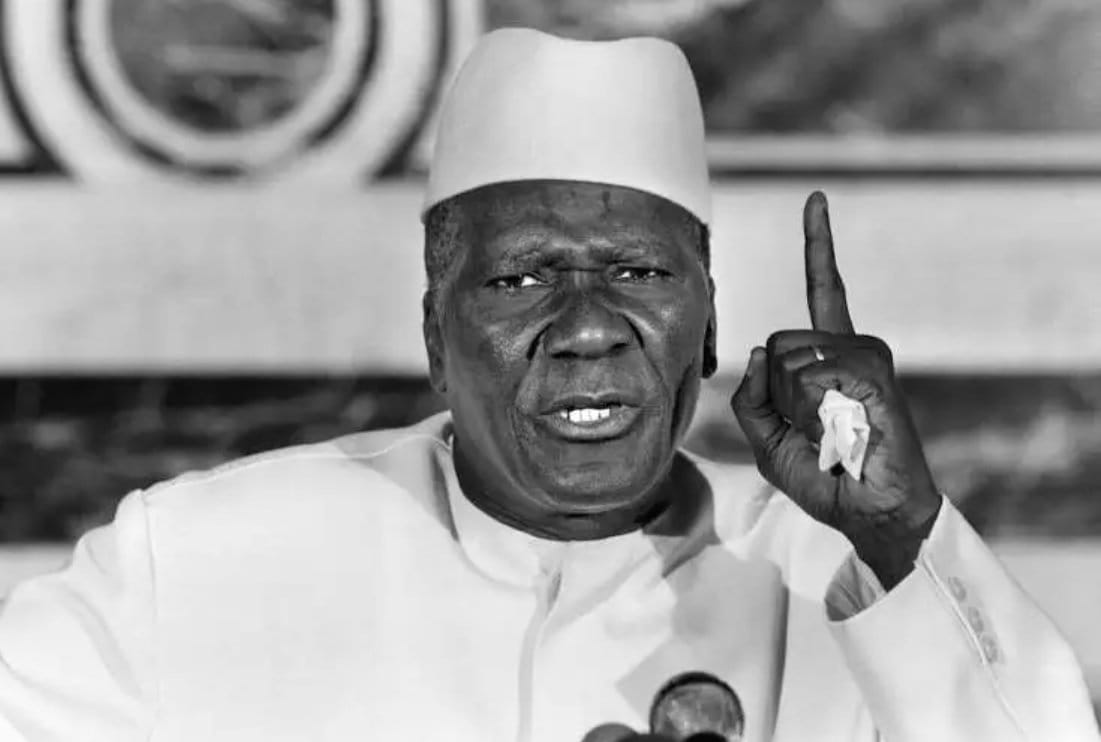

However, under the leadership of a staunch nationalist and anti-imperialist leader, Sekou Touré, Guinea chose to reject membership in the French Community and instead break away completely from France. Colonialists believed that this decision would lead to the collapse of Guinea since unlike other French African colonies, Guinea would not have any technical or economic aid from France. Yet, 66 years later, Guinea is still standing, albeit not completely uninjured.

In this article, we will discuss Guinea’s unique journey to independence.

Guinea in French West Africa

The territory known today as the Republic of Guinea, or simply Guinea, is a coastal country in West Africa. It is bordered by Guinea-Bissau, Senegal, Mali, Côte d’Ivoire, Sierra Leone, Liberia and the Atlantic Ocean. Just like its neighbours, Senegal, Mali and Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea was colonised by France and formed part of French West Africa.

When the French came, the Guinean territory was initially taken to be part of the colony of Senegal as it was administered by a French governor general in Dakar (now the Senegalese capital). Then in 1882, it became a separate French protectorate known as Rivières du Sud. By 1891, it was named French Guinea, to distinguish it from Spanish Guinea (now Equatorial Guinea) and Portuguese Guinea (now Guinea-Bissau).

From 1895, French West Africa was established as a federation of eight French colonial territories: Mauritania, French Sudan (now Mali), Upper Volta (now Burkina Faso), Dahomey (now Benin), Niger and the aforementioned territories. Senegal was likely the most important territory as its capital cities—first Saint-Louis and then Dakar—served as the capital of the entire federation.

Before World War II (1939-45), only a few French West Africans had been granted some political rights. These were people from the four oldest colonial cities in French West Africa, Saint-Louis, Goree, Rufisque and Dakar—known collectively as the Four Communes of Senegal. This is because the people of French West Africa were regarded as French subjects rather than citizens. Accordingly, the vast majority of them did not have property ownership rights, voting rights or even the right to travel to Metropolitan France.

In 1945, after World War II, the French Provisional government allocated ten seats to French West Africa in the new Constituent Assembly which was called to write a new French constitution. The ten Assembly seats were split equally between those who were French citizens and those who were not.

On 21st October 1945, six Africans were elected to the Assembly: Lamine Guèye representing the Four Communes, Léopold Sédar Senghor for Senegal and Mauritania, Félix Houphouët-Boigny for Côte d’Ivoire and Upper Volta, Sourou-Migan Apithy for Dahomey and Togo, Fily Dabo Sissoko for French Sudan (Mali) and Niger, and Yacine Diallo for Guinea.

A year later, the constitution of the French Fourth Republic was established. This new constitution allowed for all French West African territories to elect local representatives to novel General Councils. The councils had limited consultative powers and could approve budgets for their territories.

By 23rd June 1956, a French legal reform called ‘Loi Cadre’ granted universal suffrage and a few increased powers to the French African colonies. This reform was the first step in the creation of the so-called French Community.

On 31st March 1957, most French African colonies (except Togo and Cameroon) held territorial Assembly elections under the new Loi Cadre system. The leaders of the winning political parties were appointed Vice-Presidents of their corresponding Governing Councils while French Colonial Governors remained as Presidents.

The Guinean Resistance

From 1882, Samori Touré, the Mansa (meaning ‘emperor’) of the Wassolou (or Mandinka) Empire, waged war against French rule. The Mansa was ultimately defeated in 1898, sealing French dominance in the whole of French Guinea. However, decades later, his great-grandson would harness this same spirit of resistance to secure the entire nation’s freedom.

In 1946, Sekou Touré co-founded the African Democratic Rally (Rassemblement Démocratique Africain, RDA), an alliance of political parties and affiliates in French West and Equatorial Africa. The following year, the Democratic Party of Guinea (Parti Démocratique de Guinée, PDG) was formed as the French Guinean branch of the RDA. By 1952, Touré had become the leader of the PDG and begun to advocate for decolonisation, alongside the larger RDA. The RDA’s advocacy was what eventually pressured the French government to institute the Loi Cadre.

Touré and the PDG galvanised the masses to join the fight for decolonisation, since the ruling class of chiefs actually supported the colonial government. He got the backing of trade unions and farmers, leading to his election as Guinea’s deputy to the French National Assembly in 1956. He was also elected the mayor of Conakry, the country’s capital. Touré used these positions to continue to stir the public against the French colonial regime.

In 1958, the French Fourth Republic collapsed due to political instability and its failure to rein in its colonies, especially Algeria and Indochina. The Fifth Republic emerged under the leadership of then Prime Minister Charles de Gaulle, who established a new French constitution.

This new constitution would see the establishment of the French Community wherein each colony would have increased autonomy but still be strongly connected to France. The colonies would become protectorates with a National Assembly and a local ‘High Commissioner’ who was effectively the head of state.

De Gaulle presented the French African colonies with two options: join the French Community or obtain immediate, total independence. They made their choices in a referendum held on 28th September, and Guinea, under Touré’s influence, was the only colony to vote (overwhelmingly) in favour of independence.

The French quickly left Guinea en masse, withdrawing all their support and even destroying all the infrastructure that they felt they had contributed to the country. On October 2, Guinea declared itself a sovereign and independent republic, with Touré as its president. This move also led to PDG’s separation from the RDA, since the other parties supported closer ties with France.

Touré’s Contentious Rule

Touré’s leadership of independent Guinea was not without its multitude of issues. Initially, Guinea secured economic and trade agreements with the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China. By 1960, the agreements had seen nearly half of Guinea’s exports go to the Eastern bloc nations, while Guinea received millions of dollars in aid from these nations. However, when Guinea failed to become a full economic partner to the Soviet bloc by 1977, it turned to its former coloniser and other Western powers (like the US) for economic and technical assistance.

Touré turned out to be a paranoid leader who would often sanction the imprisonment and killing of his dissidents and those whom he suspected to be. His extreme approach towards dealing with perceived opponents even earned him charges from Amnesty International, on grounds of his rule being too oppressive. It is estimated that 50,000 people were killed under his regime.

Additionally, Touré declared the PDG the only legal political party in the country in 1960, meaning he ran unopposed in the presidential elections for four seven-year terms. Until Touré died in 1984, power was concentrated in his hands and that of his associates, who were mainly from the Mandinka ethnic group. Touré’s family members occupied top government posts and carted away huge amounts of public funds. By the time Touré died, the PDG no longer had the support of the now impoverished masses.

It is painfully ironic that Sekou Touré freed his nation only to subject it to cruel leadership and economic failures. Yet, he famously said, ‘Guinea prefers poverty in freedom to riches in slavery’, an assertion many Guineans would not agree with. Much like his friend Kwame Nkrumah, Touré was a pan-African hero who successfully broke his nation free from the coloniser’s hold but ultimately lacked the ability to lead it into prosperity.

Oyindamola Depo Oyedokun

Oyindamola Depo Oyedokun is an avid reader and lover of knowledge, of most kinds. When she's not reading random stuff on the internet, you'll find her putting pen to paper, or finger to keyboard.

follow me :

Leave a Comment

Sign in or become a Africa Rebirth member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.