When you think of Pharaohs, you probably picture Arab men dressed in regal headgear and garments. However, for nearly a century (circa 747 to 656 BC) the Pharaohs who ruled Egypt were Black, rulers from the nearby Kingdom of Kush in present-day Sudan.

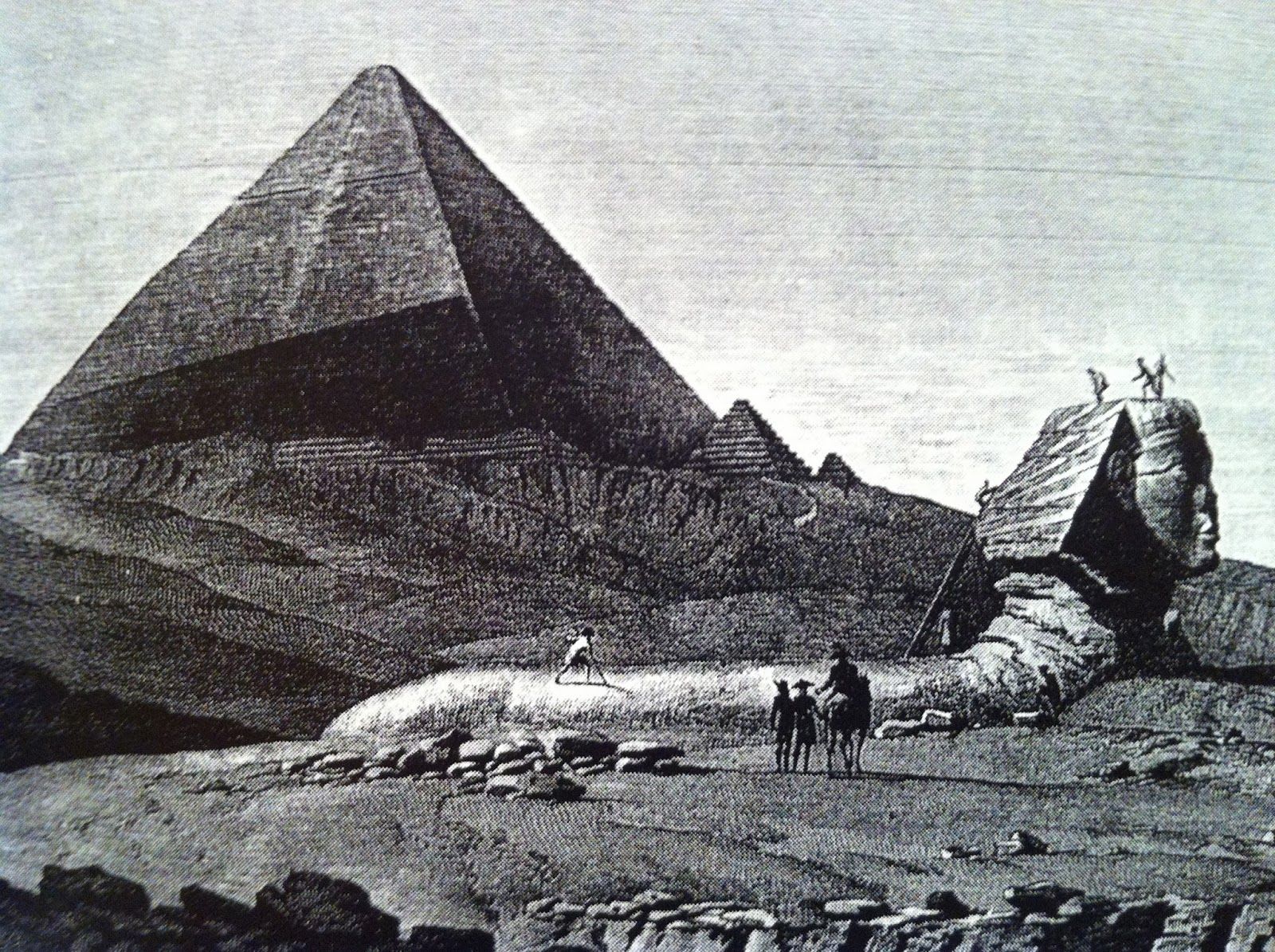

These Black Pharaohs revived Egyptian art and religious traditions, built pyramids and commissioned temples that still stand. Yet their story has been largely erased from popular narratives about ancient Egypt, just as the descendants of these Nubian pharaohs face continued marginalisation in modern Egypt.

This is the untold story of the 25th Dynasty and the erasure of Blackness in Egyptian identity that continues to this day.

The Rise of the Black Pharaohs

The Kingdom of Kush emerged as a major power during Egypt's Third Intermediate Period, when central authority had fragmented. The Kushite kings, based in Napata, saw themselves as rightful guardians of Egyptian tradition. In their eyes, they were the human sons of the god Amun with a divine mission to reunite Egypt and restore Ma’at (order and justice).

Around 752 BC, King Piye began his campaign to bring order to the chaos. His Victory Stela records how he insisted his soldiers purify themselves in the Nile and sprinkle their bodies with water from Karnak temple before battle. By 727 BC, he had captured Memphis, the traditional Egyptian capital, and sealed his victory. At Memphis, he was crowned pharaoh and proclaimed ‘king of all lands’.

Piye's brother Shabaka was the next king, fully unifying Egypt around 720-716 BC. He embraced Egyptian traditions fervently, commissioning the Shabaka Stone—now in the British Museum—which preserves the only known version of the Memphite Theology describing creation.

But it was Taharqa, reigning from 690 to 664 BC, whose rule represented the dynasty's pinnacle. The Nile flooded abundantly, producing record harvests. He funded massive building projects at Karnak and Jebel Barkal. He also built the largest pyramid in the Nubian region at Nuri, where he was buried with over 1,070 funerary figurines. Many scholars believe Taharqa is the Kushite king Tirhaqah mentioned in the Bible who aided Judah in fighting against Assyrian siege.

Cultural Renaissance and Erasure

The 25th Dynasty pharaohs were cultural revivalists who modelled themselves after rulers like Thutmose III and Ramses II. They restored temples, promoted traditional practices and brought back pyramid building in 751 BC, after it had lapsed for over a thousand years in Egypt. Today, more Nubian pyramids still stand than Egyptian ones.

This cultural renaissance ended when Assyrian forces conquered northern Egypt in 671 BC. By 667 BC, they had pushed to Thebes. The Assyrians didn't just defeat the Kushites militarily. They systematically erased them from Egyptian memory, striking their names from monuments, destroying statues and defacing stelae (monuments). The Kushite kings withdrew to their homeland, where they ruled from Napata and later Meroë for another thousand years. But they never again ruled Egypt.

The Modern Erasure: From Aswan to Kom Ombo

The descendants of those Nubians still live in Egypt, primarily around Aswan, and they continue to face systematic marginalisation. Their story is inseparable from the Aswan Dams.

When the British built the first Aswan Low Dam in 1902, Nubian lands were submerged. The dam was raised in 1912 and 1933, each time displacing more villages. But the catastrophe came with the Aswan High Dam (1960-1971). President Gamal Abdel Nasser announced it in 1956 as ‘the dam of glory, freedom, and dignity’, a symbol of Egypt's independence.

But for Nubians, it was a symbol of destruction. Between 1963-64, all 44 remaining Egyptian Nubian villages were forcibly evacuated. Around fifty thousand were displaced to Kom Ombo, a desert settlement. Forty thousand Sudanese Nubians from Wadi Halfa were relocated hundreds of kilometres from their homes.

The displacement was catastrophic. Houses at Kom Ombo were unfinished. Elderly residents and children died from harsh conditions. Families were separated. Kinship networks were severed. And beneath Lake Nasser lay the entirety of Old Nubia—villages, temples, farmland, graves.

What makes this bitter is the timing. This happened whilst Egypt positioned itself as a leader of pan-African solidarity. Nasser hosted Black intellectuals and activists. Malcolm X visited Cairo in 1964, declaring it a place where people of all complexions lived without a colour problem. Yet at that very moment, Egypt was violently displacing its own Black citizens.

UNESCO's ‘International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia’ (1960-1980) raised over forty million dollars to rescue ancient temples from Lake Nasser. But the campaign treated Nubian heritage as belonging to ‘the world’ rather than to living Nubian communities being displaced. The most valuable relics went to foreign museums. The people were expendable.

This erasure has roots in Pharaonism, a nationalist ideology that emerged during British colonialism. When British authorities treated Egyptians as racially inferior ‘people of colour’, Egyptian intellectuals responded by claiming descent from the pharaohs whilst distancing themselves from Black Africa. This racial nationalism persisted after independence, positioning Nubians as peripheral ‘others’ despite being indigenous to the Nile Valley.

Nubian Resistance and Ongoing Struggles

Egyptian Nubians have not accepted erasure passively. The Nubian rights movement gained momentum during the 2011 revolution. Nubian activist Fatima Emam recalls seeing demonstrators carrying signs in Nubian: ‘Dafi Dafi Dafi Woh Mubarak’—’Go away, Mubarak.’ It was, for her, a demonstration of the principle of citizenship.

During the 2013-14 constitutional process, Nubians successfully lobbied for Article 236, mandating that displaced Nubians be allowed to return to ancestral lands by 2024 and that the Nubian language be taught in schools. These victories were celebrated as historic.

But implementation never came. The transitional period expired in 2024 without action. Instead, Decree 444 (2014) designated seventeen villages as military zones where Nubians could not live. Decree 355 (2016) allocated return lands to private investors. When Nubians protested with a tambourine march in Aswan in 2017, twenty-four were arrested. One, businessman Gamal Sorour, died in prison.

The marginalisation extends beyond politics. In 2014, when cartoonist Fatima Hassan published racist caricatures of Black people, Nubians forced an apology through social media campaigns. But anti-Blackness remains normalised. When Beyoncé performed in Nefertiti-inspired costume, Egyptians accused her of ‘cultural appropriation’. When an Afrocentric conference was planned in Aswan in 2022, #StopAfrocentricConference trended, with Egyptians insisting pharaonic civilisation was not Black African.

These reactions reflect Pharaonism's anxieties. If Egyptian identity is defined by pharaonic descent imagined as distinct from Black Africa, then African American claims to that heritage threaten Egyptian nationalism. This logic requires denying the 25th Dynasty existed or dismissing it as aberration. It requires denying the Blackness of Nubians themselves.

Today, approximately 6% of Egypt's population—Nubians, Sudanese migrants, Eritrean and Somali refugees, Beja communities—are visibly Black African. They experience everyday racism rarely acknowledged in Egyptian discourse. Egypt officially identifies as Arab, part of the Arab League, leader of pan-Arab politics. Yet to acknowledge Nubians fully would require acknowledging that Egypt is, and has always been, an African country with Black African citizens.

Towards a More Honest History

More than 2,600 years after Taharqa was buried in his pyramid at Nuri, Nubians continue fighting for their constitutional right to return, for recognition of their language and culture and for an end to racism that treats them as foreigners in their own land.

The story of the 25th Dynasty and modern Nubian marginalisation reveals limitations in both nationalist and diasporic narratives. Egyptian nationalism has claimed pharaonic heritage whilst distancing itself from Blackness. African diaspora movements have sometimes claimed ancient Egypt without attending to Black Egyptians today.

A more honest history must hold these contradictions together. The 25th Dynasty was simultaneously Egyptian and Kushite, African and pharaonic. The Nubian pharaohs did not conquer foreign land but reclaimed shared cultural heritage. Their rule represents not aberration but a moment when deep connections between Kush and Egypt were politically embodied.

The Nubians' struggle is not just about correcting historical erasure. It is about ensuring that when we tell Egypt's story, we tell all of it—including the century when the pharaohs were Black, and the ongoing reality that Egypt's Black citizens exist, resist and refuse to be forgotten.