If you’ve ever stood before an African ivory mask or figure displayed at a European museum, you’ve likely encountered Bwami art. To art enthusiasts, these articles are striking examples of African art. But to the Lega people of eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), they are much more. In more ways than one, the articles are to the Bwami society what Nsibidi signs are to the Ekpe society of south-eastern Nigeria: abstractions that represent moral codes, and whose full meaning is revealed only to those who are initiated into the highest order.

Seeing the art without the society is like reading letters without knowledge of their language. Thus to understand the significance of Bwami art, we will first dive into the Bwami society and the larger Lega ethnic group.

The Lega People of DRC

The Lega people are a Bantu ethnic group numbering 250,000, according to 1998 records. While they’re native to DRC, they originated in present-day Uganda and started to migrate to their current location in the 16th century. They traditionally live in small village groups and are led by chiefs within various communities. These chiefs inherit their positions on a patrilineal basis, with their closest relatives having highest rank.

The Lega people are polytheistic, with various gods occupying various roles. For instance, Kalaga is known as the promiser while Kaginga is known as the incarnation of evil. The latter assists sorcerers, but the Lega believe Bwami membership makes one immune to their evil powers.

Inside the Bwami Society

Bwami membership is voluntary, but nearly universal among the Lega as over 90% of Lega adults belong to the society. Men are typically initiated into the society in their twenties, though advancement is slow and tiered. The society is divided into five principal levels: Kongabulumbu, Kansilembo, Ngandu, Yananio, and Kindi. Moving upward requires resources to host feasts and sponsor ceremonies, but members must also be known for good conduct in order to progress. Usually, the sponsorship for the ceremonies is provided by elders within one’s kinship group.

Each level of advancement is marked by initiation rites called mpala, which are performed in secluded forest sites outside the village to emphasise separation from everyday life. These rituals introduce candidates to new teachings and new ritual objects which they must commit to memory. The ceremonies are elaborate, often comprising up to eight sections.

Unlike many neighbouring orders, woman are also admitted into the Bwami society—albeit in a limited manner. A woman may only be initiated if her husband has reached the third grade (Ngandu), but once admitted she attains her husband’s level and may partake in the society’s activities. Thus, there are only three ranks available for Bwami women. Additionally, women are woven into the society’s imagery. Figures of pregnant women (Wayinda) paired with male counterparts (Kakulu ka Mpiko) appear in ceremonies, reminding initiates that gender balance is fundamental to continuity of life.

Interestingly, the Bwami believe that membership extends to the afterlife. Thus, the highest level attained in a member’s life also marks their eternal legacy.

The Moral Philosophy of the Bwami

The essence of Bwami lies in its moral code. Each level introduces new proverbs, stories, and objects that encapsulate ethical lessons. Sculptures and masks are not mere art but mnemonic devices and essentially material anchors for proverbs that guide conduct. Teachers reveal these to members in stages and typically repeat the sayings until their meanings are clear. Secrecy is built into the system such that members of lower levels are typically unaware of objects used by higher initiates.

A Bwami ivory carving. Source: Daniel P. Bieybuck

The Bwami proverbs are strikingly clear. The figure called sakimatwematwe, ‘Many Heads,’ depicts a body with multiple heads, teaching that wisdom often requires many perspectives. Another figure, the katanda, shaped like a sleeping mat riddled with holes, conveys a warning against uncontrolled sensuality. Its associated saying goes: ‘I used to love you. Fondling destroys the good ones. It has destroyed Katanda.’ In this way, objects serve as moral textbooks, condensing lessons into physical signs and symbols.

Bwami Art and its Symbolism

The objects used in Bwami initiation are small, but their meanings are vast. The materials used to make them signify their status; wooden carvings are for the lower grades, while ivory and elephant bone are reserved for the highest initiates in Yananio and Kindi.

The objects fall into three main groups:

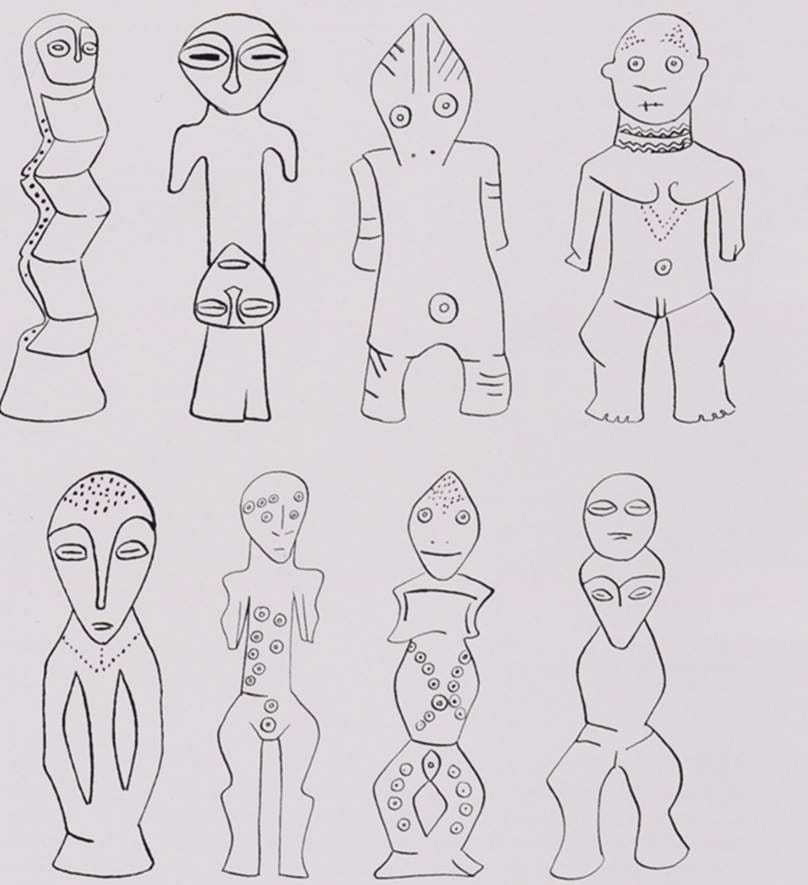

- Human Figures: These are the most common objects and are highly stylised. Some depict non-gendered figures while some like Wayinda (pregnant woman) and Kakulu ka Mpiko (the male counterpart) are displayed as pairs in ceremonies to highlight gender relations. Details such as concentric-circle eyes or lentil-shaped eyes act as distinguishing markers, and also help to recall specific associated proverbs.

Bwami human figures. Source: Daniel P. Bieybuck

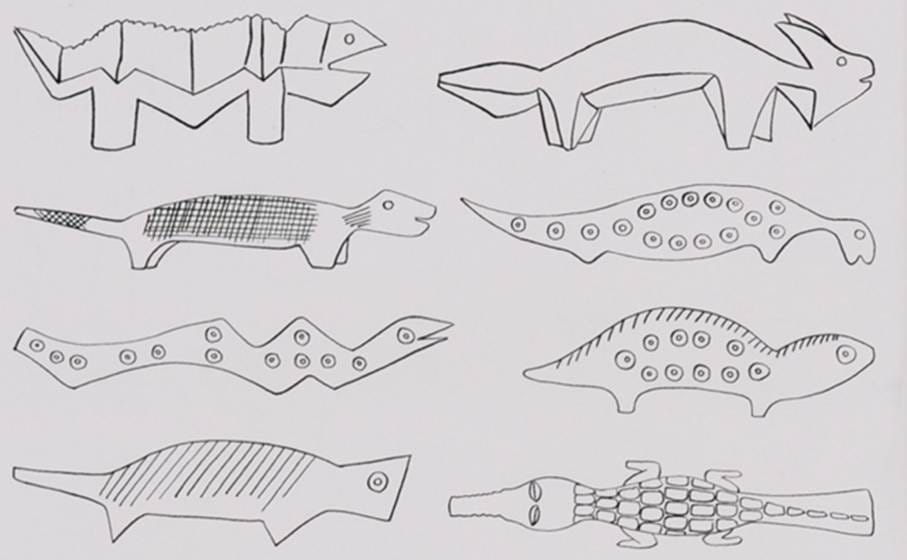

- Animal Figures: these are reserved for the highest ranks. Some are schematic quadrupeds called nugugundu while others depict specific species like dogs, pangolins, or antelopes. Only the most senior members are allowed to own bird sculptures, reinforcing their exclusivity and prestige.

Lega animal figures. Source: Daniel P. Bieybuck

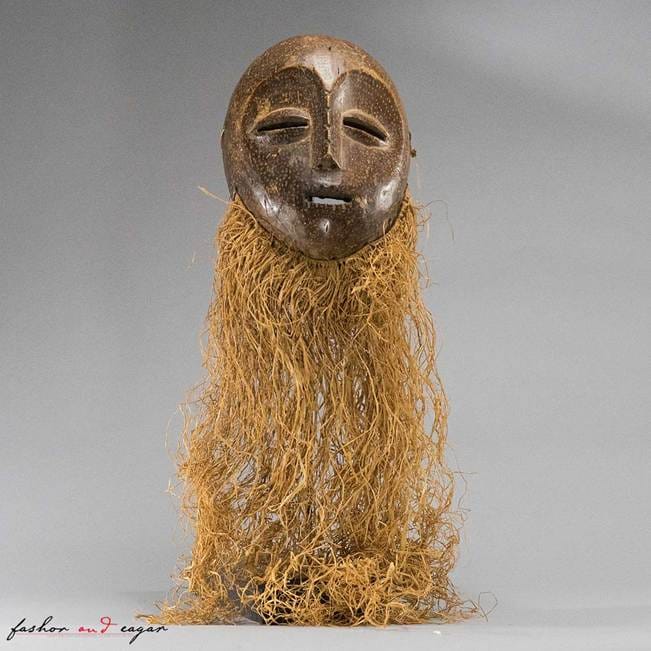

- Masks: Lega masks differ from most African masking traditions. Called lukwakongo (meaning ‘death gathers in’) and idimu, they may represent teachers, ancestors, or abstract qualities. For instance, a mask without eyes denotes an old blind elder while a closed mouth denotes a displeased teacher. A typical Bwami mask has a concave heart-shaped face. Further buttressing their relative inclusivity, Lega women are allowed to perform with masks, though only if they are wives of high-ranking members.

A Bwami mask. Source: Jean Pierre Hallet Estate Colelction via For African Art

Other items include spoons (kalukili or kakili) which are used by members of all ranks and passed down through generations. The word kakili itself means ‘inheritance’ in Lega, and the spoons symbolise the inheritance of wisdom. Interestingly, ivory spoons serve as emblems of seniority since eating porridge with them in communal settings is a visible mark of rank.

The Lega refer to their artists in two ways: mubazi wa nkondo (carver of the adze) or mulongo (person who fits things together). The artists must not be members of the society themselves. Instead, Bwami members hire them on commission and give them precise instructions. Because each object carries a fixed meaning (izu), the artist’s role is strictly constrained. Materials, shapes, and motifs are prescribed by tradition, leaving little room for personal innovation. Apprentices learn to reproduce their master’s style exactly, aiming to make works indistinguishable.

This approach explains the stylistic uniformity that so impressed European collectors. Figures are stripped down to essential forms, decorated with concentric circles, lines, or dots. What appears to outsiders as abstract artistry is in fact strict adherence to symbolic codes.

Initiation and Community Life

Bwami initiation ceremonies are communal dramas that integrate these teachings, art and performance. Candidates enter secluded forest sites where elders reveal objects, explain their meanings and demonstrate them through song and dance. Masks and sculptures are also used to animate proverbs or stories. Knowledge is imparted in steps and repetitively to aid memorisation. Because new levels can be pursued throughout life, initiation becomes a continuous process, deepening as members age.

Beyond the rituals, Bwami is the backbone of Lega society. It regulates authority, provides a moral compass, and ensures continuity across generations. Advancement within the society brings prestige, but also responsibility. Elders at higher levels wield authority not simply from age but from their moral standing within the society.

Chiefs often hold senior Bwami rank, but their legitimacy depends on having embodied the moral code, rather than just birth. In this way, Bwami balances hereditary leadership with meritocratic principles. It also provides a mechanism for resolving disputes and maintaining cohesion, ensuring that social order rests on shared values.

Bwami in the Colonial Era

DRC’s brush with colonialism disrupted but did not completely destroy Bwami. Belgian colonial authorities banned the society in 1933 and again in 1948, forcing it underground. It was not officially recognized again until 1958, by which time many traditions of Bwami art had been weakened. Still, the society endured, maintaining its teachings in secret and passing down knowledge despite colonial restrictions.

At the same time, Bwami objects entered European museums. From the late nineteenth century onward, ivory figures, masks, and spoons were collected and displayed in cities like Prague—where they are still displayed today. They were admired for their aesthetic qualities, often described as modernist abstraction. Yet stripped from context, their moral role was obscured.

The Bwami Legacy

Placed in a wider African context, Bwami stands out. While many societies mark adulthood with a single initiation at puberty, the Lega see it as a lifelong ascent. The use of small, portable objects as teaching tools also contrasts with the monumental masks or shrines of neighbouring peoples. This portability partly explains why so many Bwami objects entered European collections during the colonial period.

In the decades since, scholars and Lega descendants have been working to restore context to the significance of Bwami art. Exhibitions highlight the ways figures like sakimatwematwe or masks like lukwakongo taught lessons, not just looked striking. Just as Nsibidi cannot be separated from Ekpe, Bwami art cannot be separated from the society that gave it meaning. Rather, they form a framework through which the Lega have understood themselves and their place in the world from generation to generation.