Africa is home to quite a number of secret societies, complex institutions that have long shaped social, political and spiritual life across the continent. Among the most studied are the Poro and Sande societies of West Africa. But while these two groups are known for their oral transmission and symbolic performances, one ancient secret society in southeastern Nigeria—the Ekpe took it a step further by developing its unique writing system: Nsibidi.

Also known as Nsibiri, this ancient writing script comprises over a thousand symbols that convey everything from love to war. It has served its people in both sacred and secular contexts, serving as a unique cultural system. In this article, we will discuss how the script came to be, its various uses and enduring relevance across Africa and the diaspora.

The Origins of Nsibidi

While scholars agree that Nsibidi predates its discovery by Europeans in 1904, precisely dating its origins remains elusive. The earliest archaeological evidence of Nsibidi use comes from excavations in present-day Cross River State in southeastern Nigeria. Experts dug up terracotta vessels, headrests and human-like figures which had symbols that bore strong resemblance to Nsibidi.

Generally, scholars attribute the origin of Nsibidi to the Ekoi or Ejagham people of northern Cross River, although over the years, the writing system would also spread to the Ibibio, Efik and Igbo communities in the region.

Oral traditions of the Ejagham people, which are native to both Nigeria and Cameroon, note the existence of an ancient Nsibidi (or Nchibbidi) Society which predated the Ekpe Society. It is said that the script was revealed to them by water deities through dreams.

According to British anthropologist P.A. Talbot, its name was derived from the Ejagham word nchibbi, which he defined as ‘to turn’. Talbot believed the script was developed as a means of communication among the Ejagham people.

Over time, Nsibidi became most closely associated with the Ekpe (leopard) secret society. The nature of the Nsibidi system aligned with that of the Ekpe, a society named after the leopard because of the animal’s perceived strength, guile and, most of all, secrecy. The Ekpe men added social and political weight to Nsibidi by concealing the meaning of certain symbols to its members but displaying them in public to show the power of Ekpe.

Still, even though the Ekpe men were notorious for their use of Nsibidi, women also played an integral role in the use and invention of the symbols, though in a more aesthetic manner. The meeting places of women from both the Ejagham and Efik groups were centres where women shared the art of Nsibidi writing with other women. They would carve the hieroglyphs on calabashes, stools and various items.

The Function and Form of Nsibidi

Unlike more well-known scripts like Latin or Arabic, Nsibidi is a layered system of symbols which have a contentious classification. While some scholars classify them as pictograms, some suggest that they are better known as logograms (like Egyptian hieroglyphs) or syllabograms.

Whatever the case, the Nsibidi symbols denote meaning and logic rather than a notation of sound and speech. The symbols can generally be divided into two. The first is the basic glyphs comprising pictographic signs that can represent anything from a leopard to a mirror. The second is abstract signs like arcs, crosses and spirals that can be used to build a larger message.

An arc symbol generally indicates a person, so a combination of arcs is often used to denote interpersonal relationships. Two intertwined arcs often denote a union, love or marriage. Conversely, two separated arcs may denote a separation or broken relationship.

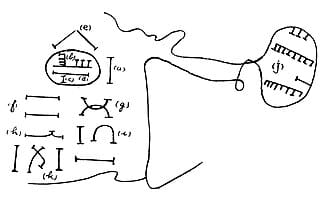

Nsibidi symbols and their meanings. Source: Africanhistoryextra.com

Symbols like double gongs and feathers are typically ascribed to leadership while manillas represent currency. Additionally, circumscribing radial accents denote the complexity of initiation into secret societies.

The system’s ability to compress information is remarkable, making it a very economical writing system. A few blocks of Nsibidi script may be translated to hundreds of words in English text. This was the case when British missionary and teacher J.K. Macgregor translated the Nsibidi script used in a judgement case known as ‘Ikpe’ in Enion, an Igbo subgroup.

Macgregor translated the image above as:

‘The record is of an Ikpe or judgement case. (a) The court was held under a tree as is the custom, (b) the parties in the case, (c) the chief who judged it, (d) his staff (these are enclosed in a circle), (e) is a man whispering into the ear of another just outside the circle of those concerned, (f) denotes all the members of the party who won the case. Two of them (g) are embracing, (h) is a man who holds a cloth between his finger and thumbs as a sign of contempt. He does not care for the words spoken. The lines round and twisting mean that the case was a difficult one which the people of the town could not judge for themselves. So they sent to the surrounding towns to call the wise men from them and the case was tried by them (j) and decided; (k) denotes that the case was one of adultery or No. 20’

Nsibidi signs can be traced with the finger, carved into wood, printed on textiles, or hammered into metals. Thus, the appearance of the symbols may slightly vary with the medium used.

Interestingly, the signs may also have multiple interpretations based on the context and ethnic group using it. Consequently, Nsibidi cannot simply be read like a book, but must be understood within its cultural framework.

Nsibidi and the Ekpe Society

Within the Ekpe Society, Nsibidi took on even more layered significance. As a secret society that historically operated like a government in parts of southeastern Nigeria and western Cameroon, the Ekpe wielded Nsibidi as a means of regulating social order.

The Ekpe took the base Nsibidi symbols and built on them, creating cryptic ‘sacred’ symbols that could only be understood by fellow members. Taking it a step further, certain forms of Nsibidi were reserved for high-ranking Ekpe members and would be inscribed during initiation rites, on ceremonial fans like the effrigi, or on the architecture of meeting houses.

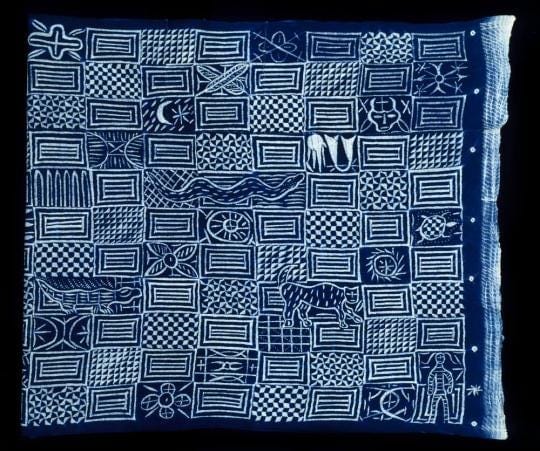

Another notable form of Nsibidi use by the Ekpe Society is in the Ukara cloth. The cotton fabric is usually dyed indigo blue and marked in white with various Nsibidi symbols in a grid pattern. The symbols often denote images of the society, powerful creatures associated with them as well as the more cryptic codes that only members can decipher.

Ukara cloth of the Ekpe Society. Source: Houston Museum of Fine Arts.

Nsibidi, Slavery, and the Transatlantic Journey

However, like most of African history, Nsibidi’s legacy is not without controversy. On the one hand, it embodies the originality and richness of African culture, but on the other hand, it has ties to one of the darkest parts of African history: slavery.

The Ekpe society and its Nsibidi-literate members were heavily involved in the transatlantic slave trade, especially in the Arochukwu arm. The Aro people, an Igbo sub-group, had one of the most prominent slave trade networks of the 17th and 18th centuries. In fact, Arochukwu infamously served as the central site for the Ibini Ukpabi (long juju) oracle, which legitimized the capture and sale of individuals into slavery.

Ekpe members in Arochukwu often used Nsibidi to communicate about slave trade dealings. The Ekpe masquerade would even be used as a slave-raiding institution. While the masquerade was being played, traders would pounce on unsuspecting viewers and capture them.

Nsibidi signs would be used to write messages on whom to capture and what houses to raid. Meanwhile, Ekpe members could declare, through secret signs, that they were Ekpe and should therefore be exempted.

This historic linkage between the transatlantic slave trade and Nsibidi is why the writing system lives on in the Americas, especially in Cuba and Haiti. Slaves who were taken to these regions continued practicing their heritage by writing the Nsibidi symbols on paper.

As early as 1812, Cuban rebel leader José Antonio Aponte was arrested for conspiring against the Spanish Crown. His personal journal—filled with Nsibidi-like illustrations—was confiscated and used as evidence.

Decades later, Nsibidi would continue to gain more ground through the Abakuá society, an Ekpe-based male fraternity founded in Cuba in 1836. Abakuá members painted the symbols on temple walls, embroidered them into garments and danced in rituals. The system has morphed, but at its core, it still maintains the visual language and spiritual authority of the original Nsibidi.

The Enduring Legacy of Nsibidi

Today, Nsibidi is experiencing a cultural revival. Visual artists, scholars and fashion designers are drawing on its visual logic for contemporary expression.

A form of ‘Neo-Nsibidi’ has also emerged: modern reinterpretations that expand and attempt to alphabetize Nsibidi. These are often seen in murals, fashion, graphic novels, and digital art. The script’s flexibility and abstraction make it particularly suited to modern artistic innovation.

Nsibidi has even inspired pop culture. In the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s Black Panther films, the fictional Wakandan language draws heavily from Nsibidi’s forms. The production designer, Hannah Beachler, studied Nsibidi and borrowed elements of its symbolism for the Wakandan set design.

Ultimately, Nsibidi continues to live—not just as a relic of the past but as a growing, morphing writing system embedded in African and diasporic identity, creativity and continuity.