In the 15th century, when Portuguese sailors first encountered the Kingdom of Benin, they were stunned. Not by "primitive" people, but by a sophisticated civilization whose citizens adorned themselves with artistry that rivaled European courts. Edo nobles wore coral bead regalia worth fortunes. Their bronze workers created sculptures of such technical mastery that Europeans initially refused to believe Africans had made them. And the women? They defined beauty through elaborate hairstyles, body art, and adornments that had nothing to do with looking European—because Europe, in that context, was irrelevant.

This was true across the continent. For thousands of years before colonial contact, African societies created their own beauty standards, as diverse as the continent itself. Beauty wasn't about approximating someone else's features. It was about cultural identity, social status, spiritual power, and artistic expression.

What did beauty look like when Africans defined it for themselves? Let's take a journey through pre-colonial Africa, region by region, and discover beauty traditions that had nothing to prove to anyone.

EAST AFRICA: Beauty as Identity, Wealth, and Endurance

The Maasai: Beadwork as Biography

Among the Maasai of Kenya and Tanzania, beauty was narrative. Every beaded necklace, earring, and bracelet told a story: marital status, age group, clan identity, even recent life events. A Maasai woman's beauty wasn't measured by her facial features but by her ability to craft intricate beadwork and adorn herself appropriately for her life stage.

Young Maasai warriors (morani) stretched their earlobes with increasingly large wooden plugs and ivory ornaments—the larger the holes, the more beautiful. This wasn't random body modification. It signaled that a warrior had endured pain, demonstrated patience (stretching takes years), and committed to his cultural identity. When a man could fit a fist-sized ornament through his earlobe, he was considered at the peak of masculine beauty.

Women shaved their heads completely—smooth scalps were considered elegant and refined. Hair was seen as unnecessary decoration when beadwork could do the job better. The contrast of dark skin against colorful beads, white chalk body paint during ceremonies, and gleaming shaved heads created the Maasai aesthetic: bold, geometric, unapologetically distinctive.

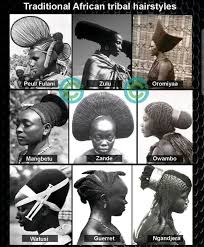

Ethiopia: Hairstyles as Status Symbols

In the Ethiopian highlands, beauty was worn on your head. Both men and women cultivated elaborate hairstyles that signified everything from martial prowess to marital status.

Warriors grew their hair long and styled it with butter and ochre into dramatic shapes—sometimes standing straight up, sometimes in elaborate braids. A warrior who had killed an enemy in battle earned the right to wear a specific hairstyle with a feather. His hair literally announced his achievements.

Ethiopian women braided their hair into intricate patterns that took hours to create and lasted weeks. The more complex the braiding, the higher the status. Wealthy women could afford to spend entire days on their hair, demonstrating that they didn't perform manual labor. Hair became a status symbol, an art form, and a social signal all at once.

WEST AFRICA: Scarification, Adornment, and Royal Aesthetics

The Yoruba: "Black Is Beautiful" (Literally)

Among the Yoruba of Nigeria, the phrase "dudu l'ewa" predates colonialism by centuries. It means "black is beautiful"—not as a political statement, but as aesthetic fact. Yoruba beauty standards celebrated dark skin, which was enhanced through various practices.

Women used camwood paste and shea butter to make their skin shine. The goal wasn't to lighten but to create a rich, lustrous glow. Yoruba women also practiced elaborate body art using indigo dye, creating temporary tattoos for ceremonies and celebrations.

Scarification was another Yoruba beauty practice. Young women received decorative scars on their faces, arms, and torsos—patterns that identified their family lineage and made them more beautiful. The scars were raised and deliberate, only visible against dark skin. This was beauty that required dark skin as the canvas.

Yoruba hairstyles were legendary. Women spent days creating sculptural styles—threading, braiding, and adorning hair with beads, coral, and precious metals. Hair wasn't just styled; it was sculpted into architectural forms. The more elaborate your hairstyle, the more beautiful, wealthy, and cultured you were considered.

The Igbo: Beauty Fattening Rituals

In Igbo culture (southeastern Nigeria), beauty preparation for young brides involved "fattening rooms." Girls entering marriage age were secluded for weeks or months, fed richly, and protected from sunlight and work. They emerged larger, with softer skin, rested, and adorned.

This practice reveals something crucial about pre-colonial African beauty standards: thinness was not idealized. Fuller figures signified wealth, health, and fertility. A plump bride was a beautiful bride because she came from a family that could afford to feed her well. Beauty was about abundance, not restriction.

The Wodaabe: Where Men Compete in Beauty Contests

Perhaps the most striking West African beauty tradition belongs to the Wodaabe people of Niger and Chad. At the annual Gerewol festival, young men—not women—compete in beauty contests.

Wodaabe men spend hours preparing: painting their faces with red ochre and white clay to elongate their features, lining their eyes with kohl, painting their lips black to make their teeth appear whiter, and dressing in elaborate beaded outfits. They then perform a dance called the Yaake, making exaggerated facial expressions to show off their white teeth and rolling their eyes to display the whites.

Women judge the competition, selecting the most beautiful men as potential lovers or husbands. The Wodaabe aesthetic prizes tall stature, white teeth, bright eyes, and facial symmetry. But here's what matters: these standards were developed entirely within Wodaabe culture, without any reference to European features.

SOUTHERN AFRICA: Geometry, Gold, and Spiritual Beauty

The Ndebele: Architecture as Adornment

Among the Ndebele of South Africa, beauty wasn't just personal—it was architectural. Ndebele women painted their homes with vibrant geometric patterns in bold colors: reds, yellows, blues, greens, arranged in symmetrical designs.

But women also painted themselves. Ndebele women wore thick beaded hoops around their necks, arms, and legs—some wearing rings that could weigh several pounds. These rings elongated the neck and created the distinctive Ndebele silhouette. Married women wore heavier rings than unmarried women, and the rings were only removed upon death.

The aesthetic was geometric, bold, and radically symmetrical. Beauty was about pattern, color, and form—not facial features or skin tone.

The Zulu: Beadwork as Language

Zulu beauty practices, like the Maasai, centered on beadwork. But Zulu beadwork was a language. Different color combinations conveyed specific messages:

- White beads: purity, love

- Red beads: passion, heartache

- Black beads: marriage, darkness

- Blue beads: faithfulness, request

- Yellow beads: wealth, beauty

- Green beads: illness, discord

A Zulu woman could literally wear her feelings, her status, and her intentions. Beauty wasn't static—it was communication. And the most beautiful women were those who mastered the grammar of beads.

NORTH AFRICA: Henna, Kohl, and Desert Elegance

Berber Beauty: Henna and Silver

Among Berber communities across North Africa, beauty was intricate and symbolic. Women adorned their hands and feet with henna designs—not the simplified patterns of modern "henna tattoos," but elaborate geometric and floral patterns that took hours to apply and days to fade.

Berber women also wore heavy silver jewelry: necklaces, bracelets, anklets, and headdresses that could weigh several pounds. The jewelry served multiple purposes: adornment, wealth storage, and protection (many pieces contained amulets and Quranic verses).

The Tuareg, sometimes called "the blue people of the desert," dyed their clothes with indigo so deep it stained their skin blue. Rather than remove the blue tint, they considered it beautiful—a sign that you wore fine textiles and belonged to a wealthy or noble family.

Ancient Egypt and Nubia: Kohl, Oils, and Royal Perfection

Ancient Egyptian and Nubian beauty practices influenced the Mediterranean world, not the other way around. Both cultures used kohl (ground antimony or lead sulfide) to line their eyes—men and women alike. The dramatic eye makeup wasn't just aesthetic; it reduced sun glare and had antibacterial properties.

Egyptians and Nubians also used scented oils, perfumes, and unguents made from myrrh, frankincense, and lotus. Wealthy individuals were buried with jars of cosmetics, perfumes, and mirrors—beauty tools were considered essential even in the afterlife.

And crucially, many of Egypt's most celebrated beauties—Nefertiti, Cleopatra, and especially Nubian rulers—were dark-skinned. Queen Tiye, one of ancient Egypt's most powerful queens, was Nubian. Her dark skin was depicted proudly in royal art. Beauty in ancient Egypt wasn't about lightness—it was about refinement, adornment, and power.

CENTRAL AFRICA: Lip Plates, Body Paint, and Forest Aesthetics

The Mursi: Beauty Through Transformation

Among the Mursi of Ethiopia, young women undergo one of Africa's most dramatic beauty transformations: the lip plate. When girls reach adolescence, their lower lips are pierced and gradually stretched over months or years to accommodate increasingly large clay or wooden plates.

To outsiders, this practice seems extreme. But within Mursi culture, a large lip plate is the pinnacle of female beauty. It demonstrates a woman's maturity, her ability to endure pain, and her commitment to her culture. Women with the largest plates command the highest bride prices and the most respect.

This practice reveals something essential about pre-colonial African beauty: beauty was cultural, not universal. What made you beautiful in one society might be irrelevant in another. And that was fine, because beauty wasn't about pleasing a global standard—it was about belonging to your people.

The Mangbetu: Head Shaping as Nobility

Among the Mangbetu of the DRC, beauty was literally shaped from birth. Noble families bound infants' heads with cloth to elongate their skulls—a process that took months but resulted in a distinctive, elongated head shape considered the height of beauty and aristocratic refinement.

Mangbetu women also removed their eyebrows and eyelashes, creating a smooth, unbroken facial surface. They wrapped their heads in elaborate headdresses that exaggerated the elongated skull shape even further. The result was a silhouette unlike anywhere else in the world—uniquely Mangbetu, uniquely beautiful.

What These Practices Reveal

Across these diverse regions, certain themes emerge:

1. Beauty was cultural identity. You didn't beautify yourself to look like someone from another culture. You beautified yourself to look MORE like your own culture—more Maasai, more Yoruba, more Himba.

2. Beauty required commitment. These weren't 10-minute makeup routines. Scarification, head shaping, earlobe stretching, and elaborate hairstyles required years of dedication. Beauty was an achievement, not a genetic lottery.

3. Beauty was about more than appearance. It signaled social status, spiritual alignment, life stage, family lineage, and personal history. Your body was a text that others could read.

4. Dark skin was the canvas, not the problem. Practices like otjize, scarification, and body painting only worked on dark skin. The aesthetic assumed dark skin as the baseline beautiful state, then enhanced it.

5. Beauty standards were local, not universal. What made you beautiful among the Wodaabe would be irrelevant among the Zulu. And that was fine. There was no single "African beauty standard" because there was no reason to have one.

The Continuity and the Break

Many of these practices continue today. Maasai and Himba women still wear their traditional adornments. Henna is still applied across North Africa. Beadwork remains central to Zulu and Ndebele identity.

But colonialism interrupted something crucial. It introduced the idea that there was a hierarchy of beauty—with European features at the top. And suddenly, practices that had been passed down for generations were labeled "primitive," "savage," or "ugly" by people who'd just arrived.

That interruption created the crisis we see today: a continent that once had hundreds of distinct, confident beauty traditions now spending $8.6 billion annually trying to look less like itself.

But the traditions didn't die. They were suppressed, but they survived. And now, as a new generation reclaims African identity, these practices are being revived—not as museum pieces, but as living alternatives to Eurocentric beauty standards.

Because here's what pre-colonial African beauty practices prove: for thousands of years, Africans knew they were beautiful without needing Europe's permission.

Maybe it's time to remember that.